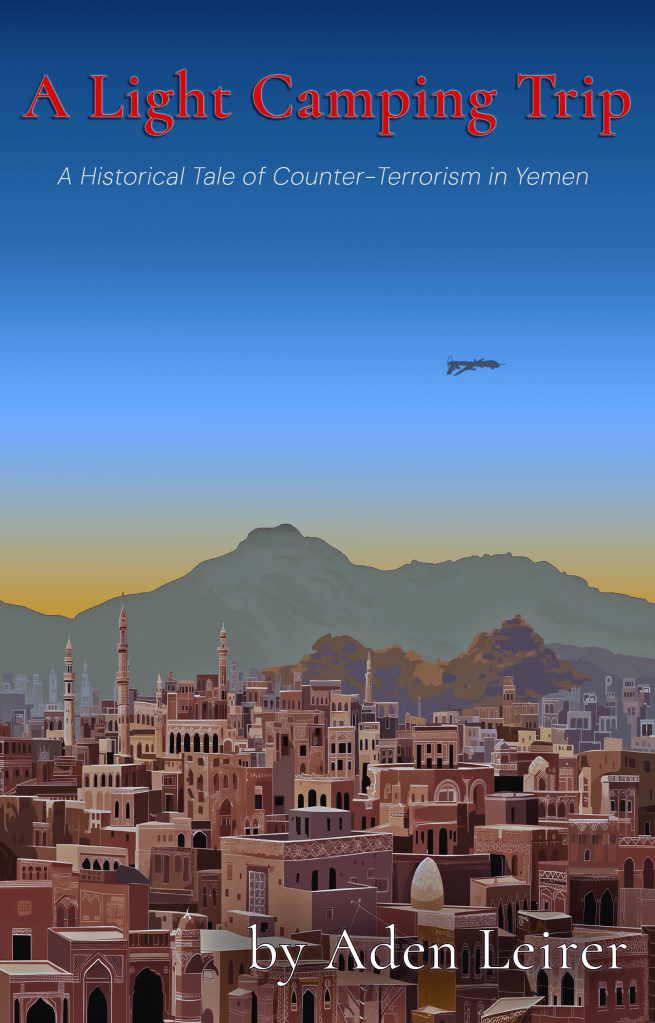

Copyright ©2013-2025 by Aden Leirer. All rights reserved.

Genre: Narrative non-fiction

Topics: Abu Ali al-Harethi assassination, Kamal Derwish, Yemen, CIA, counter-terrorism operations, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Russian organized crime, Post-9/11, Lackawanna Six, human trafficking, defense contractors.

Status: Complete, 120k words

Manuscript cleared by the CIA Prepublication Classification Review Board, June 2025.

Actively querying agents

Disclaimer: All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the US Government. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying US Government authentication of information or endorsement of the author’s views.

Historical Background:

In November 2002, the CIA conducted a targeted assassination in Yemen, eliminating Abu Ali Al-Harethi, the mastermind behind the USS Cole bombing. This mission marked the first U.S. strike on al-Qaeda outside Afghanistan and the first use of a Predator drone to kill a target beyond a conventional war zone. It also resulted in the first extra-judicial killing of a U.S. citizen, Kamal Derwish, and the first public disclosure of a CIA mission by the Pentagon. The disclosure was intended to bolster public confidence before the mid-term elections, but it had devastating unintended consequences: it unraveled U.S. intelligence networks, destabilized Yemen’s regime, and triggered a series of events that led to the rise of the Houthis and Yemen’s descent into civil war.

A Light Camping Trip takes a deep dive into this mission, focusing on its human and operational complexities. It was the first time the CIA embedded U.S. civilian linguists with a Special Operations team for an in-country counter-terrorism mission. These linguists, U.S. Navy veterans working as defense contractors, were selected for their expertise during Operation Enduring Freedom in Washington, D.C. I was one of them.

Overview:

Sana’a, Yemen. Post 9/11.

Austin and Fitz, former U.S. Navy Arabic linguists, are working as defense contractors alongside a CIA team hunting Abu Ali al-Harethi—the mastermind behind the USS Cole bombing in Yemen. Days before they leave the Capital Hotel for Yemen’s tribal lands, the mission begins to fall apart—no weapons, no body armor, and no clear answers. In the early days of the U.S. War on Terror, they navigate the shifting lines between patriotism and profiteering, sacrifice and self-interest, courage and coercion. They must decide quickly, but whatever choice they make, it could cost them their heads.

Abdallah, a front desk clerk at the Capital Hotel, dreams of moving his family to Europe. But when his fundamentalist cousin, Sahim, forces him onto a dangerous path, those dreams begin to unravel. With Sahim renditioned and interrogated by the CIA for information on Abu Ali and al-Qaeda, Abdallah must outmaneuver both the Americans and Abu Ali, as family ties are twisted into a snare.

Nevi, a Russian dancer performing at the hotel nightclub, is desperate to escape Zhadnost, a brutal trafficker and arms dealer. While the other women in her troupe have given up hope, Nevi clings to her dream of returning home. She knows there is only one way out, but it will take every ounce of strength she has left to seize it.

Time is running out. As Austin and Fitz cross paths with Abdallah and Nevi, all must face their doubts and pay a price for their beliefs.

(Note: The full text includes a comprehensive glossary for terminology, foreign phrases, and cultural references as well as a recommended reading list for readers).

Read the first 30 pages:

F.I.D.O.

Sana’a, Yemen. 2002.

Fitz cranks the door handle and shoulders his way into the hotel room. I follow a pace behind him. “Kopf’s gonna get us killed, Austin,” he grunts, whipping the room key towards the nightstand. It ricochets off the lamp and disappears with a loud clang behind the trash can. The pneumatic door hinge closes behind us with a sibilant hush.

“That’s not bullshit, either,” he says, snatching two beers out of the mini-fridge. “And I’m not betting my life that lying dick-head or his team have my back if shit hits the fan.” He tosses me a can. “Neither should you—or you might wind up getting your head chopped off.”

I slowly wipe the top of my beer with a corner of my shirt. Tiny, icy fingers dance up my spine when I realize I’m casting a shadow on the thin, translucent drapes. I move to the other side of the floor lamp to obscure my profile from the window.

Fitz drops into the wooden lounge chair next to his bed. Beer sprays when he pops his can open. “Do you believe that shit?” he gripes, with a noisy slurp. “What the hell does Kopf mean—we may not be authorized to carry?” He props his boots on the coffee table. “This is his operation. He set it up. Seriously, if I had wanted someone to blow smoke up my ass, I would’ve bought that prick a garden hose and a pack of reds back in D.C.” He forces a tight smile, but neither of us laugh.

His voice seems so loud to me, bouncing off the cinderblock walls like we’re standing at the mouth of a tunnel. I crack my beer and take a long gulp, hoping to dull the tingling sensation creeping across my scalp.

“Where do you stand with this?” he asks, focusing on me while he fishes for a cigarette in his pocket. “You haven’t said shit since we got in-country.”

He strikes his lighter several times with an irritated flick. His face glows like a beacon as he touches the flame to the tip of the cigarette. I imagine someone outside our window training a scope on the flame. I have a brief vision of the back of his head exploding to the sound of breaking glass.

“Are you high?” I snap at him, pointing to my ear, then at the windows and walls. He gives me an indifferent shrug before stretching for the remote control on the coffee table. The television blinks on with a local Arabic program. He turns the volume all of the way up.

I turn off the lamp and pull the heavy drapes closed before I sit in the chair next to him. “Look Fitz, I don’t trust them anymore than you do, but we can’t cut and run just because this op seems a little fucked. You need to take it down a notch.”

“Seems a little fucked?” he snorts, blasting a stream of smoke at the carpet between us. “Exactly how would you define totally fucked, Austin? We have no weapons, our clearances are for shit, and we’re here on tourist visas!”

He kicks the edge of the coffee table with his boot. “They don’t even know our proficiency level with the language! Either they don’t need us or they don’t care—and if either of those is true, then what the fuck are we doing here?”

His cigarette tip glows bright cherry red as he takes another agitated drag, forcing smoke out through his nose like a pressure valve. “The way I was raised, a man’s word is the most important thing he has and if he can’t keep his word with you, he doesn’t deserve your trust or allegiance.” He slices the air with the knife-edge of his hand. “That’s it, man. Peter Kopf’s a lying dick-head.”

“They’re working on it,” I reply, as I light my cigarette. “Maybe it’s like Kopf said, maybe they’re just putting this thing together on the fly, you know? You go to war with what you have, not with what you want. If you’re expecting everything to go to plan, you might be in the wrong business, my friend.”

Fitz opens his mouth but then closes it again, fixing his stare on me with one eyebrow cocked and a comment loaded. He turns away, smoking his cigarette in silence.

After several minutes he puts his feet on the floor. “Well, that’s the point, Austin. This should be a duty, not a business.” His speech is slow, like someone trying to talk while chewing on a thought they can’t spit out or swallow. “If this were a military operation there’d be some level of accountability, you know? There’d be a chain of command. But what do you do with a corporation? Who do they answer to? Should we complain to human resources? Maybe write an angry letter to their shareholders?”

He pauses for a moment, pretending like he’s deep in thought. He holds up a finger. “I know, we’ll leave them a negative review—corporate onboarding for covert op, sub-par; left royally screwed in Yemen, zero stars.”

I shake my head at him. “C’mon, Fitz—wake up. We’re not in uniform anymore, we’re contractors. This bullshit might be standard operating procedure for Company guys. We’ve got two options. We can cut and run because this op isn’t being served to us on a silver platter. Or we can grow a bigger set of balls and F.I.D.O.”

Fitz shoots me an aggravated side glance as he leans forward and taps his cigarette in the ashtray. “F.I.D.O., huh? That’s your solution to this bullshit?”

I lift my beer in a mock toast, “Fuck It and Drive On.”

Fitz lets out a heavy sigh as his face twists into a soured expression of disappointment. “I’m not sure which bothers me more, Austin—the team’s disregard for us, or Lisa pushing us for more billable hours, or the fact we’re surrounded by people who would love to parade our dead bodies through the streets.” He jabs his finger at me, “Or you—acting like this shit’s no big fuckin’ deal.”

His stare eats at me. “I get it Fitz. I do. Kopf’s a dick-head and Lisa’s a shitty rep. So what?” I stand up and lean against the wall next to the floor lamp. “There are points in life when you listen to common sense and there are times when you follow instinct.”

I take a drag and clamp the cigarette between my fingers as I point at him, “But sometimes, Fitz, you gotta ignore both and just act on belief.” The words hang in the air between us like the smoke haze catching the light from the television. “And I don’t believe they’d have us over here like this if we weren’t doing some sort of good, right? Then what’s the point?”

He rubs his thumb and fingers together in a gesture for money.

“Bull. Shit.” My patience rushes out of me as I blow smoke over his head. “They said we’d get weapons in the field. Look out the window, Fitz—we’re still in fucking Sana’a. And until we get weapons, I’m sure they’ll cover our asses if shit goes down. So stop busting balls—it’s not helping us out.”

“Well, they got ‘til tomorrow to get the handgun and body armor that Kopf promised us,” he replies, with the cigarette bouncing on his lip. “There’s no way I’m going into the field with them. No fuckin’ way. Not without a sidearm. Not without a way to defend myself. I am not going down empty handed.”

He grinds his cigarette out in the ashtray. “You do what you want, Austin, but that handgun is a make it or break it issue for me.”

Make or break issue for him. It’s not the first time he has talked about quitting, but it is the only time he has not included me.

I step away from the wall. “What does break mean?”

He turns his attention to the Arabic nature program on television, ignoring that I am still in the room, squeezing his fist in the air as if he wants to hit something or is grabbing at words he’d like to take back.

I stand for several minutes waiting for him to continue the conversation, but he says nothing. Instead, he pulls another cigarette out of his pocket and lights it. He billows a large cloud of smoke towards the television.

I give my beer a light shake and finish the last swig. I stick the cigarette butt in the can. The thin, metallic hiss is barely audible over the nature program. I rattle the can. “This room is getting to me a little bit. I’m heading down to the pool bar—you coming?”

He stares straight ahead at the television. “Nah, man, I’m good. You should go and get yourself some fresh air—maybe clear your head. I’m gonna hang here and probably chain-smoke myself into a tumor. Maybe I’ll take a nap before we meet those guys. You should check back and let me know if you think F.I.D.O. is still our way forward.”

I crumple the beer can and sling it in the trash before I yank the door open to leave. “No problemo, asshole.”

Pickled Ruminations

There are points in life when you listen to common sense and there are times when you simply follow instinct; sometimes you ignore both and just act on belief. I’ve been repeating this phrase to myself as a way of explaining how we got here. The afternoon adhan echoes across the city as I slip a pen out of my pocket and hold it, staring down at the cocktail napkin waiting for other words to form. But I write nothing. I just move the pen, tracing black lines over the empty space, slowly connecting one doubt to another until the paper is covered by a thin, Gordian knot. What if Fitz is right?

Songbirds streak from the tops of the garden trees. My body snaps tight, ready to bolt for cover as I scan the sidewalk. A thin layer of sweat coats my skin as adrenaline burns the booze from my senses.

But I see no one. Kopf’s voice rings in my head with the four sentences from the only security briefing he gave us.

You don’t blend in. The hajis would love to turn you into a trophy. Better watch your ass or we’ll see you on the news getting your fuckin’ head chopped off or strung up by your balls with your brains blown out. If anyone asks, you’re here on a light camping trip.

The hair on the back of my neck rises. Shit. I look behind me. A waiter has crouched down in the side doorway of the Indian café. He lights a cigarette as he watches me.

We are the only people outside in the courtyard. His skin is taut over the points of his skeleton. There is not an ounce of fat in his body to round out his features. He doesn’t shift his eyes from me as he continues to smoke.

I tip my drink up and finish the melted remains of my cocktail, not taking my attention from him as an ice cube spills out on the table. He doesn’t blink after several drags from his cigarette.

What? I ask with a hard twist of my face, mopping my beard with my palm and setting the glass down on the scribbled napkin. The knotted black ink bleeds into an embossed ring of condensation.

The waiter waves me back into my chair when I get up and walk towards the bar, rushing one last drag before crushing out his unfinished cigarette. His polished shoes click with a sharp cadence on the concrete as he hurries to my table. The creases in his shirt are sharp and crisp.

“Hello, Sir,” he greets with an empty hospitality smile, pulling a notepad from his pocket. “May I bring you a drink?”

“You’re new,” I remark, searching the bar behind him. “Where’s Wadih?”

“Wadih is in the nightclub.”

I hold up my empty glass with a crushed wedge of lime. “I ordered this Cuba Libre from Wadih a little while ago. I’m hoping for another.”

He continues to smile, shifting his weight and flicking the pen like a twitching tail. But he doesn’t touch the paper.

I repeat my order, listing the ingredients of my cocktail in Arabic.

The waiter stops smiling. His face drops into a slack-jaw look of surprise. He leans down close to me. “Are you a Muslim?” he asks, stepping even closer and tilting his head to match mine. A thick, black mustache makes his upper lip disappear beneath his nostrils, hiding the point where it joins the base of his nose.

“No,” I answer politely, controlling my instinct to shove him a step back.

His eyes narrow. The jaundice yellow around his dark roasted pupils makes them seem hard and ancient. He straightens. “How did you learn to speak Fus-ha?”

I lie and tell him that I majored in Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Michigan. “I enjoy speaking Arabic—to me it is the most beautiful language.”

The corners of his mouth turn up with the hint of a smile. “You are an American?”

“I was born in Denver, Colorado,” I lie again. “There are many mountains where I live. Your country reminds me of my home. Sana’a is beautiful.”

“Thank you,” he nods and points behind me. “You are not watching at this beauty.”

I turn my chair sideways, looking past the flowers along the hedge through a low section in the retaining wall. The squat city spills across the valley floor to sinopia ridgelines that pulse and breathe against the sinking, cool darkness.

“Ajmal,” I reply, gently tapping my fingernail on the cocktail glass.

“Rum?” he says, remembering my order. He takes a slight step back. “We do not have rum in the hotel.”

“I know. I buy the bottle from Wadih and he keeps it behind the bar for me,” I explain. “It’s the tall one with the blue label.”

“I’m sorry sir, that bottle is empty,” he replies with a curt shake of his head. “I do not know where Wadih finds rum. I can bring a different drink,” he offers. “We have vodka, gin, and whiskey.”

“No, thank you.”

Any of those liquors would deliver the numbness I want, but I choose this drink for other reasons. It reminds me of places far from here. Key West. Cuban food. Bare, bronze-skinned women. Fishing.

I chew on my dry bottom lip, peeling a name from a conversation I had with Wadih yesterday. Abdallah. I look up. “Wadih called Abdallah at the front desk and he finds the rum.”

“Abdallah?” he repeats, leaning in closer like we’re sharing a secret. “Wadih says Abdallah finds rum?”

“Abdallah knows where to get the rum,” I confirm, catching the waiter’s attention as I place several US bills beneath my glass.

A confident grin stretches wide across his face. “If Abdallah has located rum for you before, he can do it again.” His long, fibrous fingers close around the bills and tuck them in his pocket.

“Thank you.”

I offer the waiter a cigarette before he walks away. He stares at me, searching my face.

“Please take one,” I insist again, holding the cigarette box outstretched. “If the rum is a problem, I can drink a beer.”

He takes a cigarette.

I hold my lighter out. “Ismi Austin.” It’s a small gesture, but in a culture where context defines everything, the smallest extensions can have the most lasting impressions.

He bends down when I strike the lighter, inhaling as he straightens. The wrinkles creasing his cheekbones are pulled smooth as he draws on the cigarette.

The smile is genuine. “Shoukran,” he says. His shoulders drop as he tells me his name. Hani.

“Bi kool suror, Hani. Tesharefni,” I reply, shaking another cigarette from the pack and lighting it.

“You speak good,” he exhales with a short laugh, showing every yellowed tooth in his grin. “It is strange I hear Fus-ha from you. You are the first American I meet who speaks Fus-ha.”

“I’m learning your dialect,” I smile. “But I speak Fus-ha better.”

Hani nods as he pulls the cigarette from his lips like a cork and blows a thin, blue-gray cloud over his shoulder. “They understand Fus-ha, but people do not speak it,” he explains, shifting his weight. “You will be hard to understand how they speak at you.”

“I’m good with languages,” I smile.

“Are you here on business?”

I look in his eyes. “Yes, I’m a writer. I’m writing a travel book. I’m here on a light camping trip.”

His face snaps into the hospitality smile again. I am not a tourist and he knows it. My skin flushes hot across my scalp and down my neck. Cold sweat beads on my back.

“Aiwa, a writer?” he chuckles, arching his eyebrows. “Do you know places?” He taps his pocket with the cash I just gave him. “I know places.”

A chime sounds from the back entrance of the hotel. A couple walks down the path towards the bar. They look over at my table.

Hani stiffens. “I am not to smoke here,” he says, palming his cigarette with a furtive tuck of his hand. “I call Abdallah for the rum. I bring your beer for your wait.”

He maneuvers through the chairs before I have a chance to say anything. I have a lot of questions. Satellite imagery and State Department profiles can be useless compared to a good conversation with a local. I want to learn from someone who grew from this soil, beneath this sun. Maybe he’d see that I am not like the others.

I doubt that it would matter. Here my skin betrays me and I am guilty by association. I am just another foreigner in a line of strange faces stretching back through time. Persians. Romans. Turks. British. Soviets. Few have ever come here for the culture or the people, including me.

Including me.

I draw hard on my cigarette and replay Fitz’s words. Either they don’t need us or they don’t care—and if either of those is true, then what the fuck are we doing here?

Hani sets a beer on my table and hurries back behind the bar. The couple speaks to him for several minutes before they walk over to the Indian café. He picks up the phone and I can see him dial zero for the front desk.

I’d like to go over and continue the conversation, but I don’t. Instead, I just watch him stock beer in the cooler as he talks. I know that somewhere, at some point, we are consanguineous. Seeping down through rock and time, his blood and mine pool beneath history, where all blood flows together.

Hani holds the phone with his shoulder and picks up a knife. He cuts a lime with several quick strokes as he talks. His eyes pass over me several times, like he is giving an assessment to the person on the other end of the line.

What is it they say here? First, it is me, my brother, and my cousin against our enemies. Then, it is me and my brother against our cousin. In the end, it is just me against my brother.

Hani sets the phone down. He points the large chef knife at me and makes an awkward thumbs-up gesture. It makes his smile look a lot less amiable. Under the right conditions he’d gut me without a thought and I’d have no problems putting a bullet in his head.

Hani returns to my table carrying a loaded tray. “I have your rum.”

The tray has an assortment of glassware, a mini-bottle of cola, and some lime wedges. He arranges everything on the table. His hands are well-worked and scarred—dark skin wraps tight over his flexing tendons, fading to thick, pale calluses on his palms.

“Ashkorakum, anta akrim min kool al nas,” I say, thanking him.

“Afwan,” he replies with a broad grin, sliding the tray under his arm. “You chew Qat?”

I shake my head, “La.”

“Would you like to try it? Qat gives strength and you become smarter—you like it. I have fresh leaves, just picked today. It is excellent, the top leaves. And they’re from Wadi Darr—the best Qat, you see the insects. My uncle grows it. He is well known in the Qat market.” Hani leans down and smiles like he is about to deliver a punch line. “Maybe you write about it.”

I would like to experience Qat. It is has been woven into the social fabric of their culture for over 800 years. The locals chew on large wads of the leaves for hours and enjoy its mild, narcotic effects. During the late afternoon when Qat usage is highest, TV stations broadcast special programs designed to enhance the cerebral trip.

“Thank you, but no. It’s not that kind of travel book.”

Hani is silent and stands like he’s tempting me with a tray of desserts. A waiter walks out from the Indian restaurant and rings the small bell on the bar.

“If you want Qat, you tell me,” Hani says. “The Qat market is at the base of Mount Nuqum. I tell you where my uncle sells.”

He points across the city towards the base of Mount Nuqum. Multi-storied buildings and pisé apartments seem to grow from the hard earth. They stand as tired testaments to the arch. The Roman Empire stretched this far. A thermal haze softens their rooflines as shadows steadily fill the streets below.

The ochre buildings are exotic and strange. Gypsum curves and geometric mosaics float bright and surreal like white icing on gingerbread. Thin towers rise above the apartments and prick the skyline like thorns on a long-dead rose.

I miss Denver. I wish I was looking at the Cash Register Building instead of these minarets. Having a drink in the bier garten of Brothers Bar. Seeing women in summer dresses walking down 16th Street. Passing through a Western crowd, hearing pieces of English conversation. I miss live music—I’d love to listen to Chad Aman play at El Chapultepec.

Movement pulls my attention inside the back entrance of the hotel. A group of young women and one enormous man step out from the elevators. The Russian dancers. They turn and walk down the hallway in single file like they’re all chained together.

An ice cube cracks when I pour in the cola. The lime wedge is waxy and only squeezes out a few drops. My nose twitches when I bring the glass to my lips. They probably use this shit as engine degreaser.

The first swill is always the worst—burning its way down, coating the walls of my delicate innards and mapping my guts. Each drink is eating me away until I’ll be nothing more than an Arabic-speaking husk.

The cocktail glass sticks to the fresh napkin as I spin it and stare absently at the ice cubes. I hate the nagging doubts floating around me. No amount of rum seems to sink them, and when they do disappear, it’s only because they have dissolved into the delusional cocktail of my ego.

The hotel courtyard is below street level. Crowds of locals pass along the sidewalk above me. They are walking to the mosque for Isha’a, the evening prayer. There are more people than I can watch closely. The ornamental steel fence bordering the courtyard provides little protection. I’m swimming in a barrel.

The ethereal wail of muezzins rubs my nerves raw, serving as a continual reminder of my foreignness in this place. Quick movements on the sidewalk snag my attention—children running, the breeze catching an abaya. A slow shiver slithers down my back from the faceless eyes studying me, each with an enigmatic expression that offers no curious warmth or welcome. My heart beats like a fist pounding on a door. Knock. Knock. Time to get the fuck out.

I sign the tab over to my room, slide my tip in American dollars under the saltshaker and leave two more cigarettes on the table. The path up to the hotel is paved and out of sight of the sidewalk. I pause to watch the sunset.

Beyond the city, the arid landscape unfolds in varying shades of red and brown. Distant mountain peaks rise up behind them and extend to the horizon. This country is beautiful. In another life I could imagine living here for a while.

I take a deep breath to clear my head, becoming still, almost calm, as the dull flush of booze floods the surface of my skin. I allow myself to drink in the scenery and let it soak through me—lush greens and bright yellows of the courtyard lending to the incandescent cityscape, burning into red umber and finally doused in the soothing blue wash of evening. I stretch my senses to smell some evening sweetness, something to mark the simple beauty of the moment. Nothing. I only taste the timeless urban dust and the heavy redolence of thirsty, tropical flowers.

A hollow boom echoes from the city. Several disjointed spurts of gunfire follow. I step inside the stoop of the back entrance and stand in the shadows, holding my breath as I listen for the exchanges of a fire-fight.

The people on the sidewalk do not react. Sickly sirens wail from different corners of the city. Muezzins are still calling from the minarets. A small, black plume rises from the area where the foreign embassies are a short distance away. My buzz evaporates with the trailing column of smoke as I slip inside the back door.

The Enemy of My Enemy

Wadih sets the phone down at the maître d’ station in the hotel nightclub. He walks over to a large man seated at a table. “Your party has entered the hotel, Sayed Zhadnost,” he reports, placing an ashtray with a pack of matches on the table corner. “The man has a black beard and a mark on his neck.”

“Spaciba, Wadih,” Zhadnost spits out with a heavy Slavic accent. He points at his cocktail glass. “More gin.”

Wadih nods. “We will open the nightclub in one hour.”

“Very good.”

The club falls silent after Wadih enters the kitchen.

Man with a mark on his neck? Zhadnost repeats to himself, watching the smoke from his cigarette twist and curl in the still air. They’re sending Karim again. I hate that stuttering fuck.

Zhadnost digs in his pocket and pulls out a spent 7.62mm casing, rubbing it between his thumb and forefinger. The Soviet Army did not issue I.D. tags to soldiers when Zhadnost was deployed to Afghanistan. He wrote his name, hometown, and mother’s name on a piece of paper then slipped it inside the empty cartridge. He wore it on a chain around his neck for two years.

The large Russian rubs the brass shell like he’s trying to wear off a memory. The metal warms between his fingers as he stifles a shiver in his bones. A bloodied face appears in the darkness of the nightclub.

No one knew that poor bastard’s name. He was only a week in the field. The dushman cut off his arms and legs. They cut his krany off. They gouged out his eyes. But they left his tongue intact.

Zhadnost shifts in the seat as a sharp pain stabs his chest. The dushman used tourniquets to keep him from bleeding to death, just so we could find him alive—a nameless, shrieking stump.

The thick-bodied Russian takes a heavy pull of his gin trying to wash the bitter blood from his thoughts. No one said anything. We just untied the tourniquets. He bled out before we gave it a second thought. We collected his pieces together and they placed him in a windowless tin coffin. He was shipped back to his mother in the belly of a Black Tulip.

Zhadnost slams the rest of his gin in one gulp. Karim was probably a dushman—it’s on his face. They all had that look in their eyes. We bombed Jaji for days. Nothing was left—no plants, not a bird, not even an insect. All was scorched earth and rock. They should have all been turned to ash. But the rats had their caves.

One of the nightclub doors swings open. A silhouette stretches across the red carpet.

“Karim,” Zhadnost exhales. Sukin seyn. He slips the empty shell back into his pocket as the mujahid walks closer.

Karim Abd Al Jabiri is a man of medium build with only one notable feature. On the right side of his neck clinging to the jaw line is a gristly, keloid scar. It is larger than a quarter and has jagged edges that streak like a comet’s tail from beneath his black beard around the right side of his neck. The shrapnel that left the scar also severed a bundle of nerves in his face, leaving him to suffer with permanent, painful spasms. It is one of many reminders of his years fighting the jihad.

Zhadnost directs Karim to sit down, ignoring the urge to pull his gun and give the twitching dushman a fresh wound seven inches above his starburst scar.

Zhadnost points his finger at the mujahid. “Coffee?”

“No,” Karim replies, scanning the room before he sits down.

Wadih returns with another gin. “May I bring you anything else?”

“No,” Zhadnost replies, and waves him away. “Go smoke a couple of cigarettes.”

Karim waits until Wadih is in the kitchen before sliding a piece of paper across the table to Zhadnost. The Russian unfolds the paper, reading the list of items like he’s evaluating a hand of cards. SA-B7s. Semtex, rocket propelled grenades and launchers, fragmentation grenades, Kalashnikovs. Ammunition. He lays the piece of paper on the table.

Zhadnost takes a long drag from his cigarette and taps his finger on the paper. “Why not go to Talhi? You could buy everything there. Why come to me?”

Karim glares. “You know why.”

The Russian shrugs with a wolfish grin. “I’ve heard the Houthi tribesmen don’t like you. I’ve heard they closed the road to Sa’dah again.”

Karim sits up straight in his seat. “We ask God to permit the defeat of the Shi’a rejectionists so that the Sunnis prevail.”

Zhadnost ignores the comments and pulls a pen from his pocket. “I’ve been asked by some Americans if I know where to find Abu Ali or Abu Assam.”

“What did you…” Karim spits out before his face contorts into a twisted knot of agony. He rubs his jaw and returns his gaze to the Russian. “What–did–you–tell–them?”

Zhadnost pretends to be preoccupied with adding imaginary figures on the scrap of paper. “I told them nothing.”

“Really?” Karim leans back in his chair, still massaging his jaw. “What did they ask exactly?”

“They showed me a list. They asked for anyone connected to your Islamic Army—or whatever you’re calling yourselves now.”

Zhadnost writes a figure on the paper. “But I told them nothing. I told them it has become harder to work with the tribes, so I just handle the women now.”

“That is very good for us both,” Karim replies. “Who are the Americans?”

Zhadnost stares, “You know that answer.” He slides the paper over to the scarred mujahid. “You also know my privacy has a premium.” And here’s the premium for desperate assholes.

The mujahid frowns. A sharp inhale whistles through his lips as he curls over and clutches his face, dropping the paper on the table.

“That’s in Euros, Karim.” Zhadnost crumples the note and sets it in the ashtray. “But with the way things are going, I may start asking for gold.” He strikes a match, lighting a corner of the paper. Enjoy your pain, kahzyol.

Karim doesn’t speak. He takes several moments to catch his breath after the episode subsides. “Your prices have changed.”

Zhadnost turns his palms upward. “I am like any other business providing a very specialized service during a time of crisis.”

Karim stares at the Russian. “You’re just a vulture profiting from death.”

“Watch your mouth,” Zhadnost warns, pulling out another cigarette. “I’m in business to make money, Karim, but your money is only worth so much to me. Your name may be worth much more.”

Karim leans closer to the table, the muscles around his eyes tightening into an undisguised, hate-filled glare. His breathing is loud and heavy.

Zhadnost picks up the burning wad of paper out of the ashtray and lights his smoke. “What are you going to do, Karim?” He sets an elbow on the table and slides his other hand down to his pistol. “You can buy from me or you can go fuck yourself.”

The words feel good to say, almost as good as the familiar steel of his pistol. He tilts the barrel at Karim’s belly and rests the tip of his finger on the ridged trigger.

Karim doesn’t blink. “Maybe Abu Ali will get weapons himself in Talhi. He has jah with the northern tribes.”

“Maybe Ali can eat his own asshole—I don’t care,” Zhadnost sneers. “You’re wasting my time. Make a choice, Karim.”

The club is silent except for the Russian’s steady exhalation of smoke. He smiles at Karim while imagining the mujahid writhing on the floor, hands clutching at his stomach. A gut-shot. Then I peel the skin off your belly and wrap it around your head and watch you suffocate. Just like the dushman did to us.

Karim’s breathing slows. He leans back in the chair and nods. “We make the deal.”

Zhadnost hesitates a moment before relaxing his trigger finger. His smile fades. “When do you need delivery?”

“As soon as we can have it,” Karim answers. “Is the money going to the same place?”

“No. You are not the only ones being watched.” Zhadnost rests his cigarette in the ashtray and slides a small address book in front of Karim. The book is opened to an earmarked page filled with Cyrillic scribbling. He circles an entry and stabs it with the pen. “Call this number in the next 24 hours. Once I have payment your shipment will arrive at the airport in four days.”

“In sha Allah,” Karim says, writing the number down. “What should we look for?”

“Refrigerators,” Zhadnost replies with a sly smile. “From Plovdiv.”

Relatively Screwed

Abdallah paces behind the front desk, watching the clock on the wall as it spiders through the minutes. Blood pounds in his ears to the steady tick of the second hand. Outside the lobby windows, dusk begins to color Sana’a in monotones. He stares towards the Old City, seeing the slag-black eyes of Abu Ali in every growing shadow and the genteel threat repeating again in his mind.

Allah has blessed many men with the patience of Job, Abdallah. But in this task, Allah, in his merciful wisdom, has chosen other blessings for me. I will tell you only once—it is not Allah’s will for you to be late.

Abdallah swallows hard on a tightening lump of panic. He smooths his hands down the front of his green vest, feeling the folded sheets of paper in the breast pocket of his shirt.

I will deliver these to Abu Ali and be done with it.

The staff door opens. An older man walks across the tiled lobby. “Asalamu alaikum,” he greets Abdallah.

“Wa alaikum asalam, Mustafa,” Abdallah replies, rushing around the front desk. “You’re always late,” he complains. “And when you’re late, you make me late for things I need to do.”

“I know,” Mustafa shrugs, adjusting his shirt cuffs. “I will do better next time, Allah willing.”

“It’s always God’s will,” Abdallah grumbles beneath his breath, taking several long strides to the staff corridor. He charges into the stairwell.

“Ma salama,” Mustafa calls after him.

Abdallah descends the stairs two at a time and out through the back service entrance of the hotel. Beyond the security gate, he jogs down the sidewalk to his tired, four-door sedan. He snaps his head to three cardinal directions, left–right–front, before unlocking his car.

He drops into the driver’s seat and locks the door with an explosive breath. He sits in silence, with the heat and stale air filling his lungs, fueling the waves of anger rising across his scalp, his skin hot and hermetic across his chest rib cage, trapping all but the shortest gasps wracking his body. He hammers the steering wheel with his fists, wringing the rubber grip like a chicken neck.

“You are curse upon me, Sahim!” he barks.

A vision of his family fills his mind. He sees his wife, Nojud standing with his sons, Sadeq and Numan. The anger boiling through his body reduces into a congestive despair. I can’t lose my family.

He pats his shirt pocket, checking that the folded pages are still there. God’s curses upon you, Sahim. The car starts without complaint. He grinds it into gear.

The image of Nojud and his sons dissolves away into the burning eyes of Abu Ali. It is not Allah’s will for you to be late. Abdallah slams the gas pedal to the floor and weaves into traffic towards the Old City.

“Why did you come back, Sahim?” Abdallah hisses aloud to his empty car. “I wish you had found your martyrdom with Abu Ali. I wish you had never returned.”

Sahim had left Sana’a to join the jihadists in Pakistan over eight years ago. He never wrote Abdallah directly; instead he sent video tapes from different mujahadeen campaigns. The videos highlighted the deaths of infidels and showcased the bodies of the jihadis who died. The videos only served to inspire Abdallah to lead a life that did not follow his cousin into jihad.

Abdallah learned more about Sahim through rumors and prayers from people at the mosque. Sahim is a mujahid now, Abdallah. Your cousin fights in Bosnia, Abdallah. Allah is protecting Sahim in Chechnya. When will be your time for jihad, Abdallah?

The years passed and news about Sahim waned. Abdallah settled into the expectation that one day someone would show him a battle video with Sahim’s body wrapped in a kafa. But that didn’t happen.

It was only months ago when Sahim finally called. Abdallah had just returned home after work. The phone rang as soon as he entered the house. It reverberated like a warning bell. Abdallah paused with his hand over the phone, feeling a strange tingling in his palm, like heat radiating from a hot pan. He did not answer.

The phone rang again. And again.

He lifted the receiver. “Hello?”

“I am in Sana’a, Abdallah,” Sahim said, without any introduction. “I will be home soon.” He hung up before Abdallah had time to reply. He held the receiver to his ear for a moment, wondering if the voice had been his cousin’s. Minutes later, Sahim knocked on the door.

Abdallah opened the door and stood looking at a man he did not recognize. “May I help you?” Abdallah asked.

“I have missed you,” Sahim said, pulling his cousin close in tight hug. “I am very pleased to see you, w’Allah hua akbar, hua akrim!”

“Sahim!” Abdallah exclaimed, wrapping his arms around the older man. “Sahim! Allah was with you! I have missed you, too!” He felt how thin and wiry his cousin’s body had become over the years. “I did not recognize you—you are so different.”

“Allah has shaped me into a different man,” Sahim replied, stepping inside the house.

He looks old, Abdallah noted. There is frost in his beard. His face is weathered and hardened.

“Where is my sister?” Sahim asked.

Nojud stepped out into the hallway holding an infant. Another young boy held onto her robe. “Sahim,” she greeted with a polite smile.

“Nojud,” Sahim said, turning to his sister. He did not embrace her. “I was proud when I learned you were married to Abdallah,” he said. “Allah sent me to Chechnya, but word of your marriage reached me.”

Sahim noticed the children and smiled. “Your sons?”

“This is Sadeq and Numan,” Abdallah introduced.

“Nojud you have been a good wife, but only two?” Sahim said with a short laugh. “Allah will bless you with many more, I am sure.” He knelt and held Sadeq at arms’ length and appraised him. “W’Allah hua akbar,” he said. “They will grow to be strong servants of their Lord.”

Abdallah looked at Nojud. She shared a wary smile. “W’Allah hua akbar,” Abdallah replied. “You have been gone a long time, Sahim. Come, let us welcome you home.” He took his cousin’s hand and led him through the house.

“Have you heard from your mother?” Abdallah asked.

“I have written,” Sahim said. “Is she here?”

“The family is making the pilgrimage to Hud’s Tomb,” Abdallah said, his words reverberating through the empty house. “Then they will spend Ramadan in Tarim praying at Al Muhdhar.”

“And your mother is with her?” Sahim asked.

“No, she is with her sisters in France,” Abdallah said. “She was here for two months visiting. She is doing well.”

Sahim’s face darkened. “You let your mother live with infidels?”

“She needed treatment,” Abdallah defended. “The doctors are better there. And she lives among many Muslims.”

Sahim looked like he smelled something foul. “She should have gone to Al Muhdhar and prayed. Allah is merciful and will provide.”

Abdallah read the expression on Nojud’s face. Do not tell him we are moving to France. Do not tell him you have a job waiting for you. Do not trust him, Abdallah.

Nojud served them lunch. She sat down and set their youngest son, Numan, on her knee.

“Saltah,” Sahim said with approval. “It has been a long time since I have eaten it.” He bowed his head. “All praise be to Allah who fed us, provided us drink, and made us Muslims.”

“W’Allah hua akbar,” Abdallah said by reflex.

Sahim took a piece of the malooga bread with his right hand and scooped some of the spicy chicken stew. He ate like a man who seldom sat at a table.

“In the name of Allah,” Sahim intoned before eating. He chewed his food with slow bites and swallowed. “Praise be to Allah.”

Abdallah and Nojud sat at the table and ate in silence, listening to Sahim. He listed the many countries where he traveled and recounted the campaigns he fought. His eight years of jihad were all stories of one missed chance for martyrdom after another.

Abdallah caught himself staring at Sahim. His cousin’s face was not the face he remembered. Creases that had started years ago from laughter had folded into deep lines like hash marks. A thick scar started on one cheek and crossed his nose to the other. His eyes were the only familiar features on his face.

His mind flooded with memories of his childhood with Sahim. He was the only brother Abdallah ever had. His faith burned blindly like a gas fire on water. He pushed his passion on everyone with grand statements and rash judgments. No one was surprised when Sahim abruptly decided to test his piety through jihad. He did not even say goodbye when he left. Abdallah only found a letter on his bed.

“I remember when our fathers fought the godless infidels outside the capital and Allah blessed them with a martyr’s death, may they rest in peace,” Sahim wrote. “I remember when you and your mother and sisters moved under our roof. From that day on, you were my brother, Abdallah. I hope that I have shown you the righteous path that leads to Allah, the Merciful, and that you will choose, as I did, to follow the footsteps of the faithful.”

No one expected Sahim to stay away for long. Everyone thought he would return once he heard the sound of gunfire or slept on the cold ground for more than two nights. But each month passed and Sahim remained with the jihadists. Eventually, the expectations of his return changed into prayers for his safety and pride in his commitment.

Abdallah couldn’t help but admire his cousin’s bravery. The man who sat across from Abdallah was confident, tempered; his life seemed filled with purpose. His passion was palpable, but now it burned steady like glowing coals.

Questions churned in Abdallah’s thoughts, but he kept them to himself. Was there a defining moment that changed Sahim or did it happen over time? Could I be that brave? he asked himself. Am I living God’s purpose for me?

Nojud caught Abdallah’s attention with her subtle expression of incredulity and disapproval. He could read it in the gentle arch of her eyebrow. Abdallah held his breath as he stared at her, struck by the simple beauty of his wife holding their healthy infant. Then he looked at his older son, Sadeq. He smiled. Abdallah knew that he was witnessing his purpose.

Allah is most generous, Abdallah prayed to himself. All praise be to the Most Merciful.

Abdallah and Sahim retired to the mafraj, the highest room in the house. The room had a short couch and many cushions. The afternoon sun beamed through the rounded stained glass windows, covering the walls in myriad colors and geometric patterns. Abdallah walked over to a wooden cabinet and removed several Qat branches, handing one to Sahim.

“You must be doing well, Abdallah,” Sahim said, examining the Qat. “You can afford to buy branches now.”

Abdallah sensed reproach in his cousin’s tone. “I get this Qat at a good price from someone at the hotel.” He unfolded a damp cloth in front of him with a nervous jerk, feeling the weight of his cousin’s judgment.

“It is a good job, Sahim,” Abdallah defended, answering his cousin’s silence. He rubbed the leaves between his thumb and forefingers before picking them from the branch. “Instead of cleaning rooms, I work at the front desk.” He placed the massaged leaves between the folds of the damp cloth. “I check the guests in and assign their rooms.”

Sahim’s eyes grew wide. “Do you work with the guest register?” he asked, slipping a few Qat leaves between his gum and cheek.

Abdallah sifted through his cousin’s words for the hints of sermon. “What if I do?”

“That is a lot of responsibility—that’s all. I am proud that you are doing so well. W’Allah hua akbar.”

“W’Allah hua akbar.”

Sahim held up a Qat leaf in front of him. “But I should not have to tell you this Abdallah, a job that only serves yourself is not a job worth having.”

Abdallah’s patience began to wane. You say nothing for eight years and come back to judge me?

“It is a good job, Sahim,” he countered. “And I have a family to provide for.”

“There are more important things than money or what it buys, Abdallah,” Sahim chided. “You would do more for your family by supporting the jihad. Allah will provide for them.”

“That’s easy for you to say,” Abdallah snapped. “You have no wife or children, do you?”

Abdallah paused, taking a deep breath before he looked again at Sahim. “It is Allah who charges me with the duty to provide for my family. I am good to my wife. I am a good father. And I support the jihad. I give money at the mosque.”

Sahim assessed the situation in his mind. He held his hand up to get Abdallah’s attention. “You have in the apostle of Allah a beautiful pattern of conduct for anyone whose hope is in Allah and the last day,” he sermonized. “The Prophet, peace be upon Him, had many wives, many children, but still led the jihad.”

He shook his head at Abdallah. “You could be doing more for Allah instead of serving yourself and your interests and paying to escape your duty. You could be serving your God and helping millions of your brethren throughout the Umma.”

They sat in silence. Abdallah did not look at his cousin. Why am I angry? he asked himself. What does it matter what he says? He will leave here soon and we will probably never see him again. In a few months we will be in France and he will be off fighting somewhere. No wife. No children. He may die without knowing any of it.

Abdallah’s thoughts froze as the weight of these realizations pressed down on him. I should be thankful that I get to see him at all. I should just listen and make him happy.

Sahim felt satisfied as he watched the guilty expression hang heavier and heavier on his cousin’s face.

Abdallah did not look at Sahim but kept his eyes focused on his growing pile of Qat leaves, padding his cheeks with them in a rush to slip into kaif, the state of euphoric contentment.

Sahim waited a little longer before he chose to speak again. He changed his posture and seemed to regain his patience. “I want you to meet a friend of mine.”

“Who?” Abdallah asked, noticing his cousin’s change. He chewed on his wad of leaves and swallowed the juice.

“Abu Ali,” Sahim said with a hint of reverence in his voice. “He is a great man.”

“Is he another Wahhabi?” Abdallah asked. He had listened to many of Sahim’s mentors speak, but they were all Sunnis with the same message. “You know I do not support the Salafyists, Sahim.”

Sahim shrugged. “It is like our fathers believed, Abdallah. We are all ikwan in jihad.”

Abdallah sat up. “You have been gone a long time, Sahim. Do you know what they have been doing in Sa’dah? The Sunnis are trying to drive the Zaydis out.” He leaned forward towards his cousin. “Saleh is a traitor.”

Sahim nodded his head. “Saleh is not a Sayyid,” he said. “The blood of the Prophet, peace be upon Him, does not flow through Saleh. That is why he helps the crusaders. He is a false leader and he must be removed.”

Abdallah motioned for Sahim to recline on the cushions. “Is that what Abu Ali says? Is that why you are here? Are you going after the President?”

Sahim ignored the questions. “Abu Ali is a wise man—you can learn much from what he has to say. I have not seen him for some time. I need you to drive me to meet him tomorrow. He is in Shabwah.”

“Shabwah?” Abdallah sat up. “Into the mountains? That is a long drive just to listen to your friend talk, Sahim.”

Sahim gave a disappointed smile. “Abdallah—it has been too long since we have spent time together.” He squeezed his cousin’s hand. “Besides, it is only listening. There is no harm in listening.”

Sahim’s voice reminded Abdallah of when they were younger. He had nagged Abdallah into going with him to Al-Iman University on Fridays to listen to the Wahhabi orator, Majid Al Zindani. Al-Zindani’s red, henna-dyed beard appeared to burn as he spoke about Tawhid, the oneness of God. But his words did little to ignite Abdallah’s faith.

There is no harm in listening, Abdallah thought, waving his cousin off as he lay down on his side. And it will make him happy.

But the drive to Shabwah bothered Abdallah. This was not a Friday trip into the Old City to hear a sermon by a crazy Wahhabi. The army had gone into Shabwa to arrest Abu Ali, but instead they fought with the jihadists and were forced to retreat.

Abdallah focused on his cousin’s face. Sahim’s eyes were closed and he was leaning against the wall. His expression was serene, even with the scars.

He is just the same Sahim, Abdallah argued to himself. This is a small inconvenience to make him happy. I will do this and then he’ll be gone.

“Fine. We will go,” Abdallah finally said aloud to his cousin. “I just don’t want to talk about this anymore.”

Sahim did not open his eyes; his face broke into a knowing, satisfied smile. “W’Allah hua akbar.”

Abdallah stuffed another small clump of leaves in his mouth to ward off the knot twisting in his gut.

Sahim would not harm me.

Abdallah and Sahim passed few people during the hours they drove to Shabwah. Sahim directed Abdallah down a remote dirt road that was barely wide enough for his car. Tribesmen appeared among the outcroppings on the ridges above. Short bursts of automatic gunfire barked all around the car.

Abdallah ducked and put a hand over his head. “Sahim, they are shooting at us!” he shouted. His cousin did not flinch. Abdallah’s skin tingled and burned. He felt a cramp below his heart.

Sahim laughed at his cowering cousin. “It is fine, Abdallah. They are not shooting at us. They are just letting others know that we are coming.”

Sahim would not harm me, Abdallah repeated to himself. He sat up and gripped the steering wheel, eyeing the road ahead. There was no place to turn around.

Sahim observed his cousin. “Keep driving, Abdallah. Don’t stop again and don’t try to turn around or they will shoot at us.”

Abdallah mopped his face. Sweat ran down his cheeks, soaking the collar of his shirt. He followed the road as it wound through a deep canyon and opened into a wide, flat bottom valley with a complex of buildings in the center. There were men lined up and firing at various targets on the eastern side of the canyon. It was a training camp.

Vomit rose to the back of Abdallah’s throat. His heart jumped with each echo of rifle fire. “You brought me here to become a mujahid, didn’t you?”

Sahim shook his head. “Of course not,” he said, with a thin smile.

Abdallah swallowed hard. Kathib.

Sahim took Abdallah’s silence as an invitation to speak. “Do not be afraid, Abdallah. Abu Ali is a wise man, you will see. There are many truths in his words.” He continued talking at the window, “Ask yourself, Abdallah, who has wept for the Palestinians? Who has wept for the Iraqis? Who has wept for the Afghan children? No one—oil and tears never mix. The world only weeps when Jews and Christians are killed.”

Sahim could hear Abdallah’s heavy breathing. He reached over and patted his cousin’s forearm to comfort him. “Don’t worry, Abdallah. Supporting jihad is the duty of every Muslim, but I can’t make you a holy warrior. You may swear the bay’a; you may not. How you choose to fulfill your duty is up to you.”

Abdallah pressed his tongue to the roof of his mouth. His knuckles popped as he wrung the steering wheel with his hands.

Allah help me.

Several armed men walked out of the hospital building as Abdallah and Sahim drove into the heart of the camp. A man with a small limp stared at them as they drew closer.

He was stout with a round face. He was smiling at the other men, but the smile faded when he looked at Abdallah. Through the dirty windshield Abdallah could feel his presence. He parked the car several feet in front of the man as if this man had stopped the car with his eyes.

“This is Abu Ali,” Sahim said with reverence. Abdallah swore under his breath.

“I am going home,” Abdallah told his cousin. “I do not want to be here. I have no reason to be here. Invite Abu Ali to our house. We will have dinner and I will listen to whatever he wants to say,” he pleaded. “Don’t do this to me, Sahim.”

Sahim looked at his cousin. Abdallah shivered. He was no longer Sahim, but something colder with empty eyes that seemed carved from stone. “You are not leaving, Abdallah. I came home yesterday just to visit and see if you would permit some of our ikwan to stay with you for a short time. But I soon realized you have a greater purpose to serve. There is a reason Allah gave you your position at the hotel. You have information that we can use. It is time for you to accept your duty to your Lord.”

Sahim stepped out of the car without looking again at his cousin. Abdallah hesitated, gripping the shifter knob. One click and he could put the sedan in gear and drive away from the armed men.

But Abdallah could do nothing with his muscles. He couldn’t shift the car into drive or turn the key in the ignition. He sat like a cornered rabbit ready to spring in whichever direction led to freedom.

“Peace be upon you, Allah’s mercy and his blessings!” Sahim said as he closed the car door.

Abu Ali stepped forward. “Sahim, my brother!” he called.

The two men threw their arms around each other and kissed on the cheek. They turned and looked at Abdallah, who was still sitting in the car with the motor running.

Sahim glared at his cousin. Abdallah’s chest hurt. He took a series of shallow gulps of air, swearing beneath his breath. Abu Ali said something aloud. Sahim’s stare intensified. Abdallah shut the engine off. He opened the car door with deliberate slowness and climbed out.

“This is my cousin, Abdallah,” Sahim introduced.

“Peace be upon you, Akhi,” Abu Ali welcomed, holding his arms wide.

His smile seemed fixed like the crescent grin of a vulture, with his two burning eyes hungry and eager to get a hold of Abdallah.

The ground felt soft beneath Abdallah’s feet. His vision swam. Abdallah moved forward only a few inches with each step. Abu Ali waved him to move faster.

“Wa a’laikum asalam wa rumat Allah wa borukatuhu,” Abdallah stammered as he walked into Abu Ali’s tight embrace.

“Akhi, I want to talk to you,” Abu Ali said in a tone that made Abdallah feel like he had been punched in the stomach. He looked at his cousin. Sahim shared a satisfied grin that tore at Abdallah’s heart.

Abu Ali took Abdallah’s hand and Sahim’s, turning away from the building to lead them on a walk through the camp. The two men reminisced about their time with the Sheik in Khost. Sahim had told Abdallah that he met bin Laden several times, but Abdallah thought his cousin was just trying to impress him.

The more Abu Ali talked about Sahim, the more Abdallah realized that his cousin was a stranger he had let back into his life. Fear pressed heavier and heavier on him with each breath.

Abu Ali led them past the ranges along the road that eventually ended in a berm that overlooked the empty valley. He stopped walking and turned to Abdallah. “For years the Russians and the West have used us to fight their economic wars. The Russians gave us weapons and money as long as we told them we supported the Communists. They had almost 5,000 troops here in the 80s.”

He spoke like he was giving a history lesson. He pointed to the camp and swept his arm in a small arc. “They trained political groups here like the Saudi Communist Party and the Bahrain Liberation Front. Over 3,000 Cubans were here. They trained the People’s Front for the Liberation of Oman in this very camp. There were East Germans and Russians training groups from Palestine and Somalia, too.”

Abdallah said nothing. He stared across the valley. Abu Ali’s voice seemed very distant.

Abu Ali stopped talking. Sahim smacked Abdallah on the shoulder to rouse his attention. Abu Ali continued to speak when Abdallah made eye contact again. “Did they give us this training to help us? Of course not. The Russians trained these fighters so that they would start political revolutions in their homelands and spread their godless economic doctrine throughout the Umma.”

Abu Ali paused to scratch his beard and pointed at Abdallah. “They expected us to fight each other because they gave us money. They have always underestimated us. They have always treated us like we were stupid.”

His laugh was harsh and derisive. “Instead we went to the holy land of Khurasan and with Allah’s help their flag was folded and thrown into the trash. The world watched the Russian infidels brought to their knees by the will of Allah. Then we returned home and overthrew our government, w’Allah hua al akbar.”

“W’Allah hua akbar,” Sahim repeated.

Abu Ali shook his index finger. “As it is written, Abdallah—remember how the Unbelievers plotted against you, to keep you in bonds, or kill you, or drive you from your home. They plot and plan. Allah plans, too. The best of planners is Allah.”

“Allah is all knowing and merciful,” Sahim said.

Abdallah turned around, letting his vision follow the road back in the direction of the city. He stared at the dark blue canopy that draped across the sky to the horizon.

Abu Ali placed a hand on the young man’s shoulder. “You might ask yourself, Abdallah—what can I do when I am so far from the fields of jihad?”

Abdallah stopped breathing when the older mujahid squeezed his shoulder paternally. The muscles in his body tightened in anger like a twisted rope doubled over. His jaw ached.

Abu Ali continued to speak. “One hour fighting under the banner of jihad is worth more than 60 years of nightly prayer. But fighting the jihad does not always mean firing a rifle. The enemies we are seeking to destroy are the kufar you are serving.”

He stared directly into Abdallah’s eyes. “You know their names, their personal information, their rooms, their vehicles and their movements. With this knowledge you can be a source of strength to us. This advantage will give you a decisive role, Allah willing, in serving the religion of your Lord.”

Abdallah did not reply. He felt gravity release him, his stomach turning over, his body floating away into the blue expanse above him. His gaze drifted over Abu Ali’s shoulder to the sinking rim of the horizon. It looked like the closing lid of a coffin.

He trailed his eyes across the camp to his car. There was no one in sight. For an instant he pictured himself pushing Abu Ali down the incline of the berm and smashing Sahim with a rock. He envisioned driving back to Sana’a, collecting his family and taking the next flight to France. Allah help me.

Abdallah’s senses honed to a razor’s quick. He searched the ground and found a fist-sized rock near his feet. Adrenaline charged his muscles and his breathing quickened, keeping pace with his racing heart. He took a step to the side, putting Abu Ali and Sahim into position.

“Abdallah,” Abu Ali said with a knowing expression, stepping away from the berm edge. “Stand with the righteous that serve Allah. If you do not, you will have not only betrayed Islam and Muslims and left the fold of faith, but the blood of countless Muslims and countrymen is on your hands. Our external enemies are taking advantage of your heedlessness as you sell your fellow Muslims out for the crusader’s wages.”

He set both hands on Abdallah’s shoulders and dug in with his fingers. “Takfir, Abdallah. You will be an enemy of Islam and God’s justice will be swift upon you and your family. His justice knows no mercy.”

Sahim’s stare was piercing. “Allah’s hand stretches across the world—even into France.”

Abdallah caught his breath like a dagger had been jammed between his shoulder blades. He stared at Sahim, holding back an angry scream. His cousin’s eyes were flat. He will harm me to get whatever he wants.

Abdallah slid a hand over his heart, expecting to find the point of a knife jutting out beneath his breastbone. Nojud Nojud Nojud he repeated, trying to lose himself in the distance. He wanted to wake up from this hell–dream, feel the weight and warmth of her body against his, the greedy pull of her arms wrapped around him.

“You would hurt my family?”

“Takfir,” Abu Ali repeated.

Abdallah closed his eyes and saw Nojud holding Numan. His nose was filled with the sweet scent of Sadeq’s skin. His heart ached to feel them near him again. Then he saw Abu Ali standing in the doorway of his house with a blood-streaked blade in his hand.

Abdallah’s throat tightened as spots swirled in his vision. He struggled to breathe. “I will do whatever you want,” he choked. “Please don’t hurt my family. Bismillah, don’t hurt my family.”